Malcolm X, an exceptionally keen critic of imperialism, clearly discerned in the 1960s that modern warfare is predominantly psychological. “One of the best ways to safeguard yourself from being deceived,” he advised his audience at the Militant Labor Forum in New York (1965), “is always to form the habit of looking at things for yourself, before you try to come to any judgment. Especially,” he added:

in this kind of country and in this kind of society which has mastered the art of very deceitfully painting people whom they don’t like in an image that they know you won’t like…. The FBI can feed information to the press to make your neighbor think you’re something subversive. The FBI – they do it very skillfully, they maneuver the press on a national scale; and the CIA maneuvers the press on an international scale…. They master this imagery, this image-making…. You let the man maneuver you into thinking that it’s wrong to fight him when he’s fighting you. He’s fighting you in the morning, fighting you in the noon, fighting you at night and fighting you all in between, and you still think it’s wrong to fight him back.1

Malcolm’s observation of the low-intensity ubiquity of war – in the form of image-making, media manipulation, and the art of deception – and of its covert nature – operating at a level hidden from everyday consciousness – resonates with the “Grim Epigram” with which Nick Dyer-Witheford and Svitlana Matviyenko introduce their 2019 study, Cyberwar and Revolution. “You May Not Be Interested in Cyberwar…” the authors observe; but cyberwar is monitoring your every move. This being the case, it is in your interest, both Malcolm and Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko agree, to return the attention that cyberwar is giving you and become yourself interested in cyberwar.

Let us begin with the subject of Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko’s Grim Epigram: war. In conventional (and misleading) terms, modern warfare is waged on a Westphalian nation-state model: nation-states have the right to wage war against other nation-states. But in reality, there have always been non-state, quasi-state, and para-state actors involved in modern warfare.

This point should be emphasized. When it comes to the agency or agencies behind war’s interest in you, the everyday civilian, contrary to common belief, these agencies are not simply state agencies. That is to say: wars are not waged between, for example, “the U.S.” and “China.”

Rather, agents of war assemble and mobilize non-state, quasi-state, and para-state war machines.

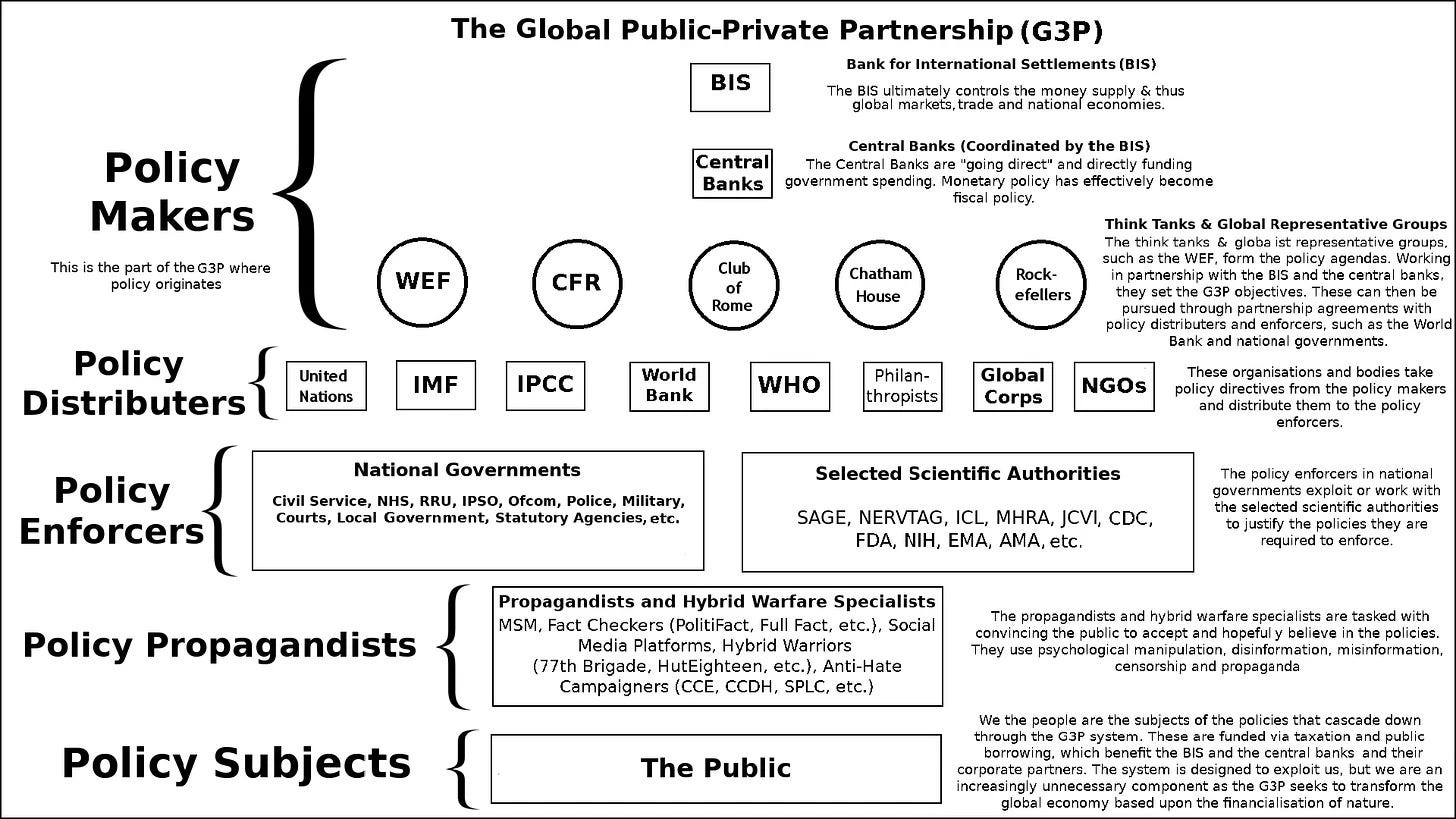

War machines are “polymorphous and diffuse organizations,” which may involve political parties; nonprofit organizations like the Rockefeller Foundation and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; transnational networks like the World Economic Forum; multinational corporations like Pfizer, Meta, and Alphabet; financial institutions like Central Banks, the IMF, and Bank for International Settlements; shareholder groups like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street; military intelligence agencies; and para-state biosecurity apparatuses like the World Health Organization – all of which “enjoy complex links with the state form.”2

Invariably, the stakeholders of such organizations are more interested in pursuing the advantage of their own transnational class – for example through global “public-private partnerships” – than they are that of the nation into which they happen to have been born.

This point is made with reference to conventional, kinetic wars by, for example, Anthony Sutton in Wallstreet and the Bolshevik Revolution (1974) and Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler (1976).

But the consolidation of post-Westphalian public-private syndicates is more advanced today than it was during the WWII era of which Sutton wrote. Following the advent of cybernetics, newly pioneered cyber battlescapes have given rise to a new paradigm of war – or at least the addition of new and complexifying layers to the Westphalian nation-state model of conventional warfare.

Updating how we think about war, Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko conceptualize the emergence of cybernetics in contemporary warfare as inaugurating not so much an altogether new paradigm of war as a new era of “hybrid cyberconventional wars.”3

“Cyberwar” is also known by other names, including “information war,” “netwar,” and “iWar.” “We favor the term cyberwar,” the authors explain:

because it emphasizes the new centrality to war of digital technologies, thus pointing back historically to origins in Second World War and Cold War cybernetics and forward to other new levels of networking and automation likely to characterize all social relations, including war making, in the twenty-first century.4

So understood, the authors’ theorization of cyberwar may be said to point back to Norbert Weiner’s Cybernetics: or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (1948), nicknamed by some the “Cybernetics Bible,” and forward to theoretical trends to which they hope their work will contribute following from the 2016 publication of Benjamin Bratton’s The Stack.5

The actual term “cyberwar” – as distinguished from “cybernetics,” “cyberspace” and other cognate terms – first appeared in a January 1987 edition of Omni magazine in an article titled, “Robotic Warriors Clash in Cyberwars.”6 The term “cyberwars” was provided by Omni creator and editor, Bob Guccione (who, as it so happens, also created Penthouse magazine). The article itself was written by Owen Davies. The terms appeared again in a September 1992 article by Eric Arnett, “Welcome to Hyperwar,” published in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. A year later, the term “cyberwar” appeared yet again, this time in Comparative Strategy, in a prophetically titled article by John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, “Cyberwar is coming!”7 A final early cyberwar document of note, in and through which the term takes on increasingly expansive definitional content, is the RAND Corporation’s 1996 scenario-based exercise, “An Exploration of Cyberspace Security R&D Investment Strategies for DARPA.”8

From Arquilla and Ronfeldt’s “Cyberwar is coming!” (1993):

Suppose that war looked like this: Small numbers of your light, highly mobile forces defeat and compel the surrender of large masses of heavily armed, dug-in enemy forces, with little loss of life on either side. Your forces can do this because they are well prepared, make room for maneuver, concentrate their firepower rapidly in unexpected places, and have superior command, control, and information systems that are decentralized to allow tactical initiatives, yet provide the central commanders with unparalleled intelligence and “topsight” for strategic purposes.

For your forces, warfare is no longer primarily a function of who puts the most capital, labor and technology on the battlefield, but of who has the best information about the battlefield. What distinguishes the victors is their grasp of information – not only from the mundane standpoint of knowing how to find the enemy while keeping it in the dark, but also in doctrinal and organizational terms. The analogy is rather like a chess game where you see the entire board, but your opponent sees only its own pieces – you can win even if he is allowed to start with additional powerful pieces.

The cloaking power of cyberwar here imagined reflects one of its quintessential characteristics. In the pithy formulation of Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko: “Digital war is a veritable fog machine,” involving cyberwar operations that are “exceptionally deeply cloaked” and often intended to confuse or ‘keep the enemy in the dark’. Obscuration, obfuscation, misdirection and the like are all fundamental cyberwar operations. A number of techniques may be mobilized to this end, including intentional false flag operations; misinformation, disinformation, and/or information saturation campaigns; planting red herrings; and fabricating “conspiracy theories.”

So pervasive are these types of operations that the authors are led to the disorienting conclusion that “cyberwar is a weaponization of information that always threatens to destroy truth.”9

Watch “Tom Cruise Hyper-realistic DeepFake” video (2 min. 23 sec.):

Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko’s description of cyberwar as a threat to truth complements that of Robert Kaiser, who argues that “since 2000, cyberwar has named an emergent knowledge power assemblage, mobilizing institutional powers, lavish budgets, and lucrative career paths.”

Combining these descriptions, I take cyberwar to name an adversarial knowledge-power ensemble that is exceptionally deeply cloaked, enjoys advantageous informational topsight, and always threatens to destroy truth through various weaponizations of information.

Or, adopting a slightly different formulation, cyberwar can be described as covert knowledge practices conducted by interlocking state, para-state, sub-state and/or non-state war machines that weaponize information to wage a profitable war on truth.

And this cyberwar ensemble is interested in you – the “datafied subject” – who it takes as its target. As Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko explain, part of what it means for cyberwar to be interested in you is that it “seeks its own advantage through you” via surveillance, profiling, data collection, biometric toolkits, “digital subterfuge” and “machinic destruction of the truth.”10

Mobilizing an “automated apparatus of completely impersonal scale and speed,” agents of cyberwar seek their own advantage through you, and in so doing, reduce you to an object of algorithmic expropriation and exploitation.11

As discussed, the agents waging cyberwar should not be spoken of “in terms of the intentions or desires of ‘China’ or ‘Russia’ – as , of course, of the ‘United States’, ‘Canada’, ‘Ukraine’, ‘Saudi Arabia’,” or any other nation. Such attributions must rather be understood as “shorthand metonymic mystification of ruling-class power.” Concretely, this power is identified by the authors as having accrued to “‘our oligarchs, who even live in the same parts of Manhattan,” despite having diverse national and ethnic affiliations.12

Cyberwar, then, as one of the ruling class’s recently minted means of waging war, is interested in seeking its advantage through you – the datafied subject – in order to compel you to labor within its knowledge-power ensemble, which tends to destroy truth, until you become superfluous – or threatening – to its needs.

Vibe of the day:

Malcolm X, Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements Edited with Prefatory Notes by George Breitman (Grove Press, 1965), “At the Audubon,” pp. 92-93. Emphasis mine.

I borrow the concept of war machines, with modifications inspired by Achille Mbembe, from Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (University of Minnesota Press, 2018 [1980]); quotes are from Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Duke University Press, 2019 [2016]), p. 85.

Cyberwar and Revolution (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), p. 5.

Ibid., p. 28.

Ibid., pp. 25-26.

https://ia601709.us.archive.org/33/items/omni-archive/OMNI_1987_01.pdf.

https://www.rand.org/pubs/reprints/RP223.html.

https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR797.html.

Cyberwar and Revolution, pp. 7-8. Emphasis mine.

Ibid., pp. 6-11.

Ibid., p. 18.

Ibid., pp. 19-21. Emphasis mine.

So good!!